Rozanne Hawksley

THE POETRY OF TS ELIOT means a great deal to Rozanne Hawksley. Yet after our conversation, it is the words of Sean O’Casey that echo in my mind. ‘Man’s inhumanity to man makes countless thousands mourn.’ A long remembered quote from exam years that stood out as a discordant phrase within the text, yet one which has remained when all else has been forgotten. There is something very true to Rozanne in this. Her work is often a discordant presence, yet has the capacity to resonate long after the moment of encounter. Mention her name, and the response will be of the enduring impact of Pale Armistice (1987, 1991), the visceral anger of A Treaty will Shortly be Signed… (1997) or the studied reflection of The Seamstress and The Sea (2003/4). For some the work is too difficult to view but for others, often those affected by the issues being addressed, there is a profound connection. A shared recognition at something plucked from the depths of human experience that is ‘offered up’ to another in the making of a response.

Rozanne is a singular artist who has steadfastly pursued her own path, creating only the work she ‘has to make’. The subjects she tackles are huge: life and death, especially the inhumanities of war, poverty and the abuse of power. The media she uses is diverse, determined solely by the work and the idea or feeling with which she is grappling. Every piece is different and each inhabits the contested territory where textiles, craft and fine art intersect. ‘I regard very strongly that stitch and fabric is one of the media that is a means to express whatever we want to say. Stitch is incredible and beautiful on its own – as a painting or engraving is – but I don’t think we should see it as something separate. I am uneasy about the division of what is craft and art. There are superb craftsmen, and it is not to say their work is any lower than whatever fine art means. I think perhaps the difference is that maybe the person who calls [themselves] an artist is using a craft plus a great deal of thinking in an abstract way – that there is something going on in the heart and mind that they need to externalise.’ This is Rozanne’s approach.

‘I REGARD VERY STRONGLY THAT STITCH AND FABRIC IS ONE OF THE MEDIA THAT IS A MEANS TO EXPRESS WHATEVER WE WANT TO SAY. STITCH IS INCREDIBLE AND BEAUTIFUL ON ITS OWN…’

Her skill levels are high, her sensibilities acute. Trained in fashion at the Royal College of Art (1951-54) she received a rigorous grounding in materials and pattern-cutting. ‘I hated the maths but loved the three dimensionality of fashion – like a subtle form of engineering.’ The RCA and later teaching at various colleges, brought her into contact with couture houses and the work of Jean Muir, Hardy Amies and Yves Saint-Laurent. ‘They knew what the body and fabric could do. That cloth could do this…’ Teaching also brought her into contact with Goldsmiths’ Textile Department where she examined alongside Constance Howard. ‘She encouraged me to take a three week summer course. I knew there was something else out there and when I joined the course I thought – this is it.’ The discovery coincided with a severe breakdown. It was a harrowing time but a key experience in the development of her practice. ‘That’s when I started stitching. Things I’d seen as child in Portsmouth came back quite vividly.’ Working in the print room at Goldsmiths’ under the guidance of David Green – ‘he was a pioneer if anyone was’ – Rozanne began to create mixed-media pieces examining human suffering, Please Look After Mr Syd (1978) being an important early work. Constructed of wood reclaimed from a skip, and based on the idea of a man evicted from his home, it contains all we have come to expect from Rozanne: an unflinching eye, unconventional materials, the combining of two and three-dimensional forms, something hidden. ‘I like the physicality of making – living and thinking something out of your mind into material form; translating out of your heart and mind.’

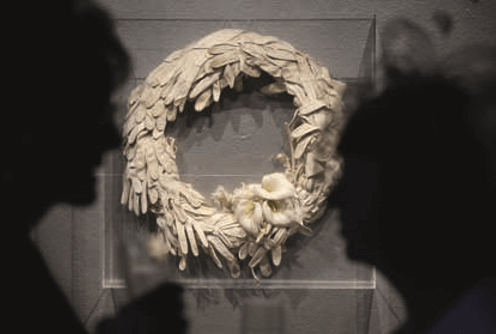

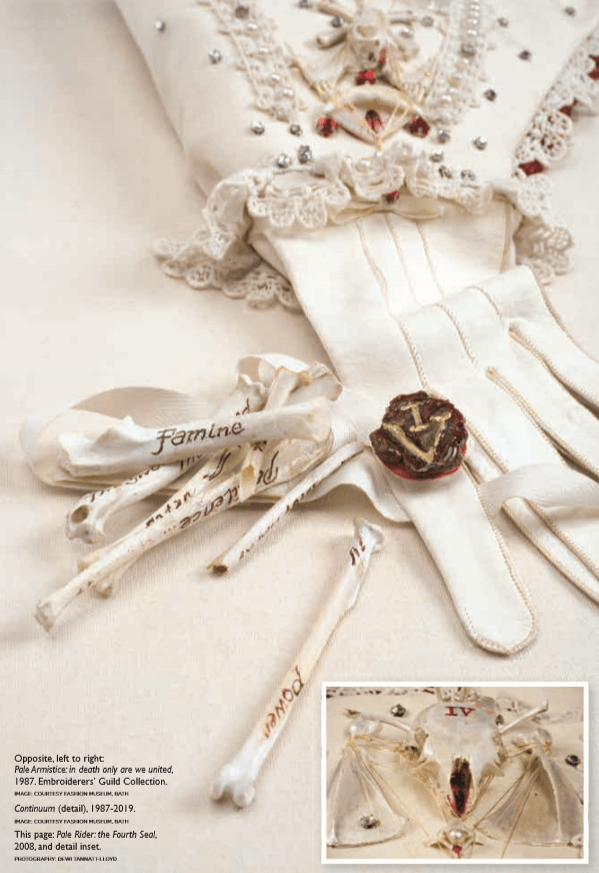

The craft of making is important, but it is the idea conveyed that is vital. ‘Whatever it is that I look at and see in the making of a piece, there’s something I want to say – a little jewel next to a beautiful gold thread or very fine neutral thread combined with a bit of bone – they’ve got a bit of the world that I’m talking about.’ ‘Talking about the world’ is central to Rozanne’s work. Not as idle chatter but as an informed, compassionately angry, commentary on human existence. ‘The interest in life and death has been with me for so long, it’s part of my nature.’ People isolated and alone are one concern, those affected by oppression and conflict another. ‘I do think of war a lot. I can’t help it.’ Growing up in a maritime port during the 1930s exerted a deep influence. Witness The Seamstress and the Sea, a major work that formed the Imperial War Museum’s first art installation on board HMS Belfast (2006-7) and was subsequently acquired by the National Maritime Museum. Based on research around Rozanne’s grandmother, a pieceworker who sewed sailors’ collars at home, the exhibition explored the impact of war on all involved – sailors, civilians, medics. It remains an archetypal work. Rooted in a knowledge of textiles, it uses that same knowledge to transcend the medium and offer different understandings of human experience. It is a quality perhaps best demonstrated by Rozanne’s signature glove pieces. ‘A glove is a person to me, in whatever situation they are in.’ A dozen of these diverse works currently feature in the Year of the Glove at the Fashion Museum, Bath, an insightful exhibition that places the artist’s practice alongside the Worshipful Company of Glovers’ Collection of historic gauntlets, which have inspired 30 years of work, notably et ne nos inducas…(and lead us not…) (1987-9) and Aimez-vous le Big Mac? (2008).

‘I AM MORE AND MORE AWARE OF HOW MIRACULOUS THINGS ARE IF WE LEAVE THEM ALONE’

The latter is a memorial, a form frequently referenced. A diligent researcher, Rozanne has extensive knowledge of mourning traditions, from the paper glove wreaths made for young girls in England to the elaborate rituals of southern Spain. All feed into her work. In recent years, however, the focus of mourning has shifted to the destruction of nature with environmental change (Caiaphas, 2014). ‘I keep remembering Alan Bennett’s wonderful lines in Forty Years On describing the hedges coming down from the silent fields and a butterfly as an event.’ I am more and more aware of how miraculous things are if we leave them alone.’ More recently, with political turmoil compounded by ill health, has come a period of creative block. ‘I’ve been waiting for that recognition of a spark of something I see or imagine – that spark of excitement mixed with dread which I need to have.’ There is recognition of this as another mourning, a loss of self; something which the artist typically aligns with the experience of others, before speaking of ways to counter the impasse. ‘It occurred to me to go searching through drawing for a while.’ There is, she explains, ‘one more piece I want to make’. The conversation with the world may have paused, but it has certainly not ended.