Amanda Cobbett

Although Amanda Cobbett enjoys replicating decay in her work, she’s not so keen on having it arrive on her doorstep, gifted in the form of ‘fungi people think I might like. Thoughtful – but by the time I receive them they’re not at their best.’

Honouring the beauty inherent in natural forms, notably fungi, lichen and moss, in hyper-realistic machine embroidered stitch is an integral part of Amanda’s daily life, stemming from the hours she spends walking with her dog, seeking out natural treasures. Amanda has long ‘thought in 3D’. Her father, a draughtsman with a ‘fantastic, ramshackle workshop’ taught her three-dimensional drawing. At school she enjoyed sculpture, making a wire and metal fish using an arc welder discovering heat's additional possibilities, realising she could melt things with a soldering iron. ‘I burned paper, plastic and other things I probably shouldn’t have been doing.’ These days Amanda’s got to grips with how far she can push her materials. ‘Don’t burn wool – it ends up in nasty little bobbly bits – synthetic’s better for melting. My threads are generally rayon, so they work well with heat.’ Although Amanda enjoyed sewing with her mum, she had no natural desire to study textiles after her foundation year. ‘I thought if you did textiles you’d become a dress designer or make curtains. I didn’t have the patience to thread up a loom for weave so I went into print. I'm all about instant gratification. That's why machine embroidery suits me; the needle goes at breakneck speed. I sew around 130,000 stitches a day.'

Although Amanda Cobbett enjoys replicating decay in her work, she’s not so keen on having it arrive on her doorstep, gifted in the form of ‘fungi people think I might like. Thoughtful – but by the time I receive them they’re not at their best.’

Honouring the beauty inherent in natural forms, notably fungi, lichen and moss, in hyper-realistic machine embroidered stitch is an integral part of Amanda’s daily life, stemming from the hours she spends walking with her dog, seeking out natural treasures. Amanda has long ‘thought in 3D’. Her father, a draughtsman with a ‘fantastic, ramshackle workshop’ taught her three-dimensional drawing. At school she enjoyed sculpture, making a wire and metal fish using an arc welder discovering heat's additional possibilities, realising she could melt things with a soldering iron. ‘I burned paper, plastic and other things I probably shouldn’t have been doing.’ These days Amanda’s got to grips with how far she can push her materials. ‘Don’t burn wool – it ends up in nasty little bobbly bits – synthetic’s better for melting. My threads are generally rayon, so they work well with heat.’ Although Amanda enjoyed sewing with her mum, she had no natural desire to study textiles after her foundation year. ‘I thought if you did textiles you’d become a dress designer or make curtains. I didn’t have the patience to thread up a loom for weave so I went into print. I'm all about instant gratification. That' why machine embroidery suits me; the needle goes at breakneck speed. I sew around 130,000 stitches a day.'

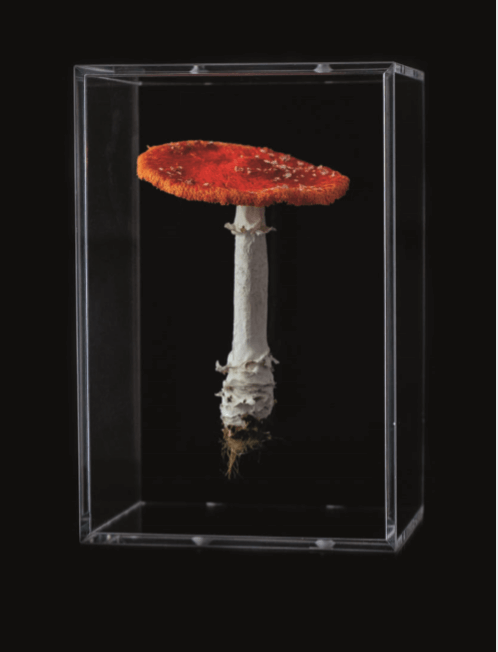

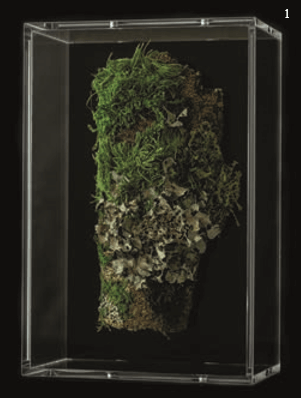

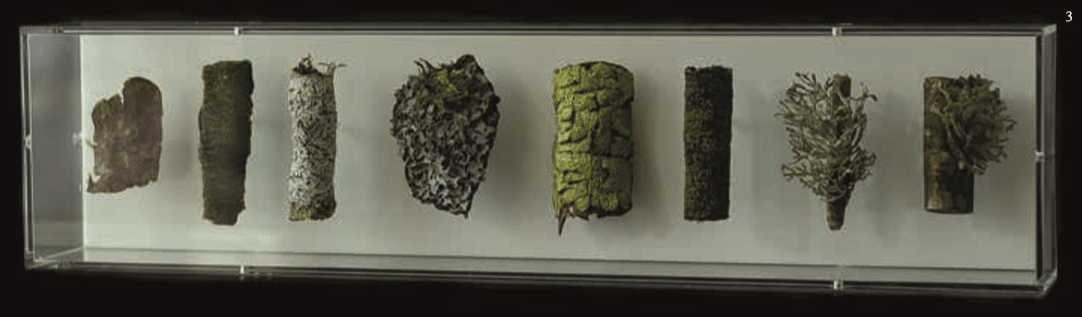

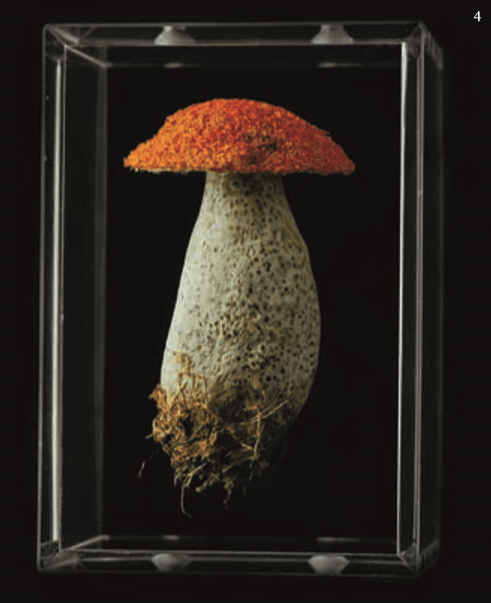

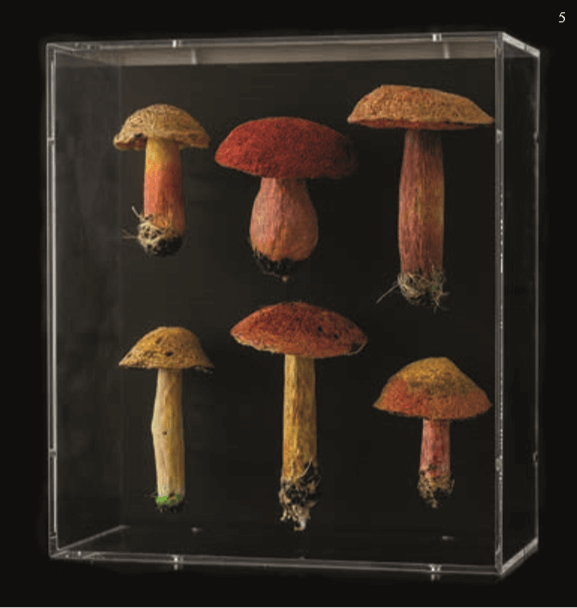

Early workshop experience proved handy as Amanda uses tools as confidently as her machine he uses a drill press to help accurately mount her work on rods within bespoke Perspex boxes, which are her version of Victorian specimen display cases. For most of her working life Amanda was a print designer and she always sought ‘to push the possibilities of a material. I used to print with puff binders, iron filings and foils. It’s always been about texture: how can I make this feel nice? I do it in the forest, picking things up, working out the texture in my hand, trying to recreate it. As a child I drove my mum nuts with pine cones and oak apples in my pockets and all over my bedroom. She’s since said at least that’s all come to something useful,’ Amanda smiles. Successfully freelancing for 12 years in print design, Amanda found some aspects of it increasingly dispiriting. ‘Once you’ve designed the print you have no control. It loses the thing you wanted it to be. As soon as the work left my hands it I felt it lost integrity, wasn’t of me any more.’ However it taught her about precision. ‘My work now is still precise, with less straight lines maybe.’ Echoing architect Frank Gehry she likes ‘the natural world because there aren’t straight lines’. The move from print to three-dimensional textiles was a slow transition. ‘Although disenchanted with print, I still loved designing and wanted to do something creative.’ Moving to the countryside and raising her family caused Amanda to reconsider career priorities. Inspiration arrived in the shape of a gifted Bernina via her mother in law, who introduced Amanda to the world of non-traditional embroidery and dissolvable fabric. She began experimenting with creating freeform embroidery on water soluble fabrics applied to papier mâché bases, and revelled in the fact she’d found a way of working creatively at home. She started by making birds, but felt she couldn’t make them believable. Beneath the surface though, ideas and earlier experiences were quietly growing, like the flora around her 'Walking in the forest with my dog is my thinking time. I wanted to capture the beauty of what I was seeing. At college I’d enjoyed privileged access to Kew’s microbiology department but the specimens were squashed, dried out – disappointing. I was also inspired by Overbeck’s amazing collection of birds, insects, even a dodo - incredible specimens but sad - butterflies cruelly pinned down so we can enjoy their beauty. I wondered how can I pretend I’ve preserved [a specimen] but not be cruel?’

Amanda seeks to capture the essential life force of whatever she’s depicting. She has a strong idea in mind then researches how she might produce it. The pockmarked stalks of her beloved Boletus mushrooms are a case in point. ‘Pushing a pyrography tool onto the stem made of papier mâché covered with one or two silk layers gives that lovely burnished finish'. If the mark's too black she paints over it using custom blends from her collection of inks, Procion dyes and pens. An online query on ‘tools that burnish’, triggered the purchase of a pyrography tool ‘for about ten quid’. Experimenting with it was a eureka moment: ‘I was so excited – I could achieve a realistic look by selectively burning or melting fibres'. Many embroiderers use heat to add texture, colour and even selectively destroy, such as when Amanda uses it to cut out lace-like frond shapes in Tyvek, but the delicacy of her pyrographic mark making takes this methodology to a whole new level. So realistic are her pieces that renowned mushroom specialist Roger Phillips and horticulturalist Stefan Buczacki have said ‘nice things about my work, so it must be alright,’ she says modestly. Amanda always uses the Latin names for her stitched ‘specimens’ and spends hours online identifying finds. She's even been asked to speak at The British Mycological Society. Her audience now encompasses the worlds of both horticulture and art, especially following her appearance at the Chelsea Flower Show, where she sold enough work to sustain her for an entire year. Intrigued and mystified by the realistic nature of her work, international customers enquired about the customs regulations of taking what they thought were attractively preserved specimens out of the country. ‘Everything is paper and thread. People often think the lichens and moss are worked over bark. They just can’t believe it’s all stitched.’ Although Amanda’s work is hyperrealistic, she enjoys including more unusual elements that reflect her personality.

'I love light-reflective thread's thickness and how it stands out in the dark, like the grey bit on high-vis jackets. I like that people buying my work will get that element of surprise later. I don’t tell them about it beforehand.’ And, as you might expect, she has a huge collection of threads. ‘I love discovering different things. I buy a lot from Barn Yarns. I use Madeira, Kimono silk, invisible thread, not much silver and gold, just a little bit in the bobbin, partially to avoid shredding but mostly to provide ‘a little bit of pickup on the surface, tiny specks, nothing too dominant. I’m also excited about a new polyester thread I can use with polyester fabric and heat treat to shrink and melt.’ Despite this expansive approach, Amanda doesn’t consider herself an embroiderer in the classical sense. ‘I’m an accidental embroiderer. I didn’t mean to do it. I’m making it up as I go along but somehow it kind of works. I don’t play by the rules because I don’t know what the rules are.’ Contented customers across the globe would beg to differ.